Looking for Grammar in all the Right Places

Published:

Interpretability

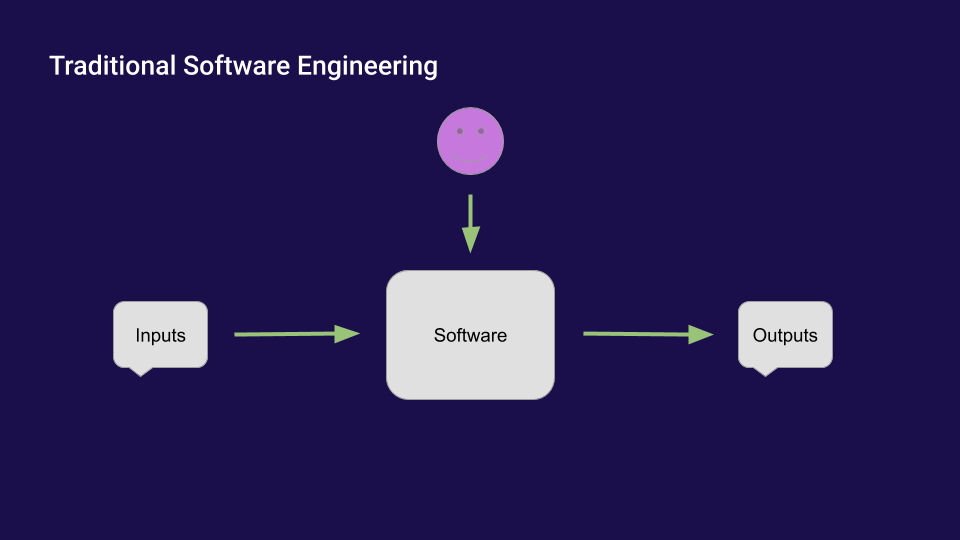

Over the course of the OpenAI Scholars Program, I became fascinated with Interpretability. Interpretability is like “mind reading” for neural networks. It’s about looking inside of networks to understand how they represent and process information. This is difficult because of how different deep learning is from traditional software engineering. In traditional software engineering, a human being writes software, and that software takes inputs and gives outputs. (If the software is a word processor, the inputs are keystrokes and clicks and the outputs are documents. If the software is a search engine, the inputs are search quesries and the outputs are links to webpages.)

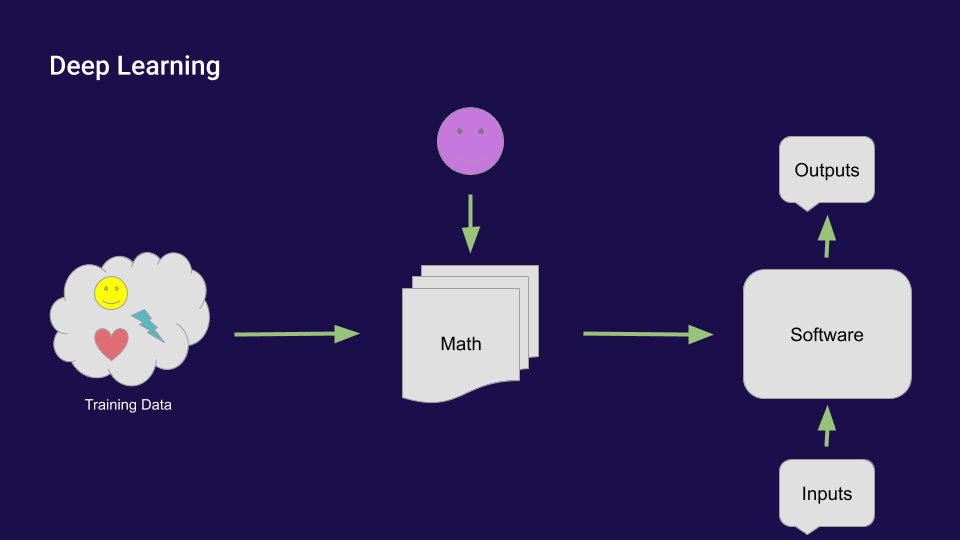

In deep learning, a human being creates math and feeds a bunch of training data through that math. Tthe data, the math, and the computer(s) create a piece of software, which takes inputs and outputs. The human being does not directly create the software and consequently does not plan how it will work and (most likely) does not even know how it works:

It’s much harder to understand software created by math than it is to understand software created by human beings.

But it’s also extremely important to understand how AI systems in our lives work. These systems have a huge impact on our lives.

GPT-2 Interpretation

I’m particularly fascinated by transformer-based language models, so I decided to try my hand at interpreting GPT-2, a transformer-based language model which had state of the art performance when it was released by OpenAI in early 2019. As a tractable first project, I decided to look for how GPT-2 understands English grammar. For a lay-person friendly explanation of transformers, and GPT-2 in particular, I encourage you to watch the short talk I gave about this project, here:

For a deeper dive into transformers, I recommend The Illustrated Transformer.

Datasets

I decided to look at GPT-2’s representations of simple part of speech, detailed part of speech, and syntactic dependencies. To accomplish this, I began by building three large datasets of sentences, one for each of these categories. First I started with the Corpus of Linguistic Acceptability, which is a widely known dataset that labels sentences as grammatically and incorrect. I dropped all of the grammatically incorrect sentences and kept only the grammatically correct ones. Then I tokenized these sentences using spaCy and the GPT-2 BPE tokenizer. I only kept sentences whose spaCy tokenization resulted in the same number of tokens as the GPT-2 tokenization. In other words, sentences that had a one-to-one correlation between words + punctuation marks and GPT-2 BPE tokens. Then, for each sentence, I labeled that sentence with the list of spaCy token.pos_ (simple part of speech), token.tag_(detailed part of speech), and token.dep_ (syntactic dependency) tags for each token in the sentence. For the final puctuation mark, I kept the punctuation intact. So here’s an example of how a sentence would get labeled for each dataset

Example sentence: “I enjoyed this project!”

| Dataset | Sentence Label | I | enjoyed | this | project | ! |

| simple parts of speech | PRON|VERB|DET|NOUN|! | PRON (pronoun) | VERB (verb) | DET (determiner) | NOUN (noun) | ! |

| detailed parts of speech | PRP|VBD|DT|NN|! | PRP (pronoun, personal) | VBD (verb, past tense) | DT (determiner) | NN (noun, singular or mass) | ! |

| syntactic dependencies | nsubj|ROOT|det|dobj|! | nsubj (nominal subject) | ROOT (None) | det (determiner) | dobj (direct object) | ! |

Then I used openwebtext to download a few months worth of webtext websites. Then I extracted the sentences from those, and added each sentence to my datasets if and only if (1) the number of spaCy tokens in the sentence matched the number of GPT-2 tokens in the sentence, and (2) the label for that sentence matched a pre-existing label in that dataset for a grammatically correct sentence from CoLA. Finally I split each of my three datasets into train, validation and test sets and ended up with:

| Dataset | Labels/Grammatical Structures | Training labels with > 500 sentences each | Total Training Sentences | Total Validation Sentences | Total Test Sentences |

| simple parts of speech | 2,837 | 104 | 222,794 | 15,903 | 16,017 |

| detailed parts of speech | 3,162 | 60 | 125,756 | 8,948 | 9,226 |

| syntactic dependencies | 2,643 | 157 | 333,427 | 23,962 | 24,119 |

Measuring Grammatical Understanding

After building these three datasets, I replaced the language modeling linear layer on top of GPT-2 with three other, independent linear layers which output probilities of grammatical tokens like this:

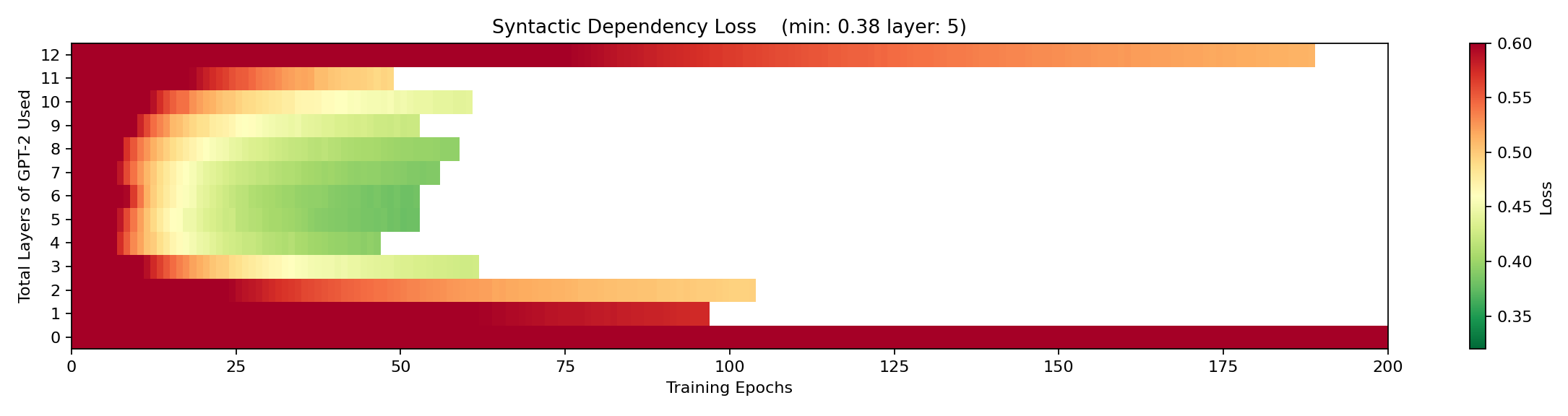

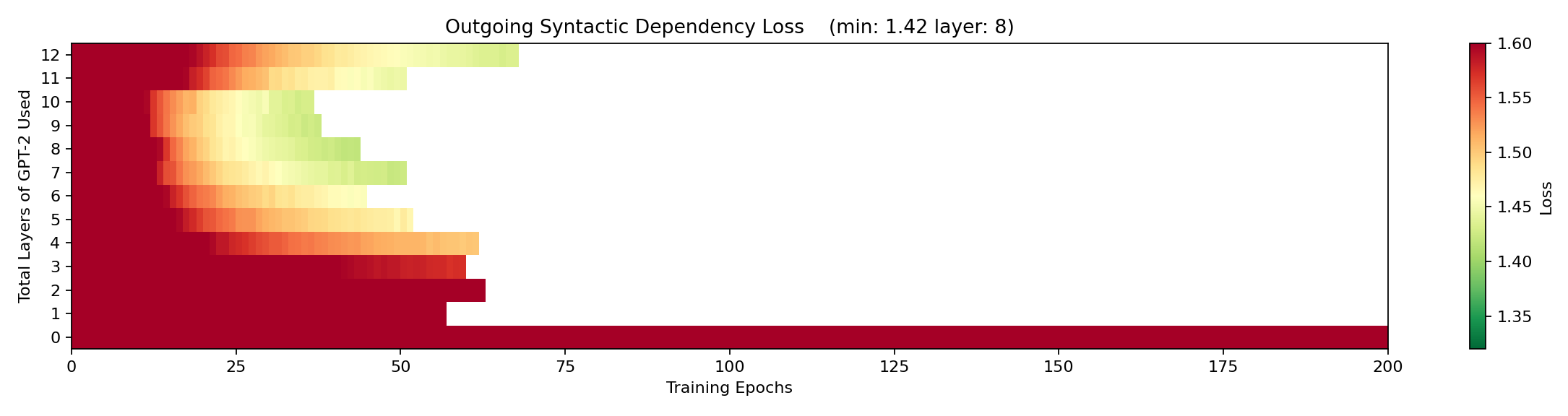

I then froze GPT-2 and trained each of my grammatical classifier linear layers using cross-entropy loss. I recorded the loss after each epoch of training. In addition, I repeated this training process on top of each transfomer layer, as well as on top of the imput embedding (using no transformer layers of GPT-2). I looked at how slow/difficult it was to train these classifiers on each transformer layer and found that they trained the fastest and achieved the best loss on the middle layers of the network. Here’s what that looked like for syntactic dependency loss:

The horizontal axis here is epochs and the vertical axis is the number of transformer layers of GPT-2, from 0 transfomer layers (directly on top of the input embedding) to 12-transformer layers (all of gpt-2 small). The color goes from red (high loss), to green (low loss). The syntactic dependency classifier has a progressively easier and easier time classifying the incoming sentence as we increase through the first five transformer layers of GPT-2, until it got its best overall score (in the fewest epochs) at layer 5. Then at higher layers, it starts to have a harder time again.

This made me think the first half of the network might be focused on understanding the incoming tokens and the second half of the network might be focused on producing the outgoing tokens. Since GPT-2 is built to generate probabilities of subsequent tokens in each position, I tested my theory by shifting the grammatical labels one position to the left (so they would better match the outgoing tokens) and repeating the experiment. And here’s what I saw:

When the classifier was trying to produce the grammatical structure of a likely output sentence, its loss was high in the first half of the network and only got better in the second half, with the best loss score coming at layer 8. This was convincing evidence that the first half of the network was, indeed, more focused on the grammar of the incoming tokens and the second half was more focused on the grammar of the outgoing (probable) tokens. In addition, this gave a small validation that the training results for my linear layer do serve as a viable measure of informational availability at each transfomer layer.

It’s also interesting (and makes sense) that the outgoing classifier scored a much higher loss than the incoming classifier. Since the network does not deterministically produce output tokens, and since future input tokens are not allowed to impact past output positions (by means of attention masking in GPT-2), this means that the output is more flexible and less precisely defined than the input. So it makes sense that it would be harder to definitively say that the output token will match the grammatical structures of the input sentences. This is all a long-winded way of saying that it’s harder to describe the future than the past, because the future is not precisely known the way the past is.

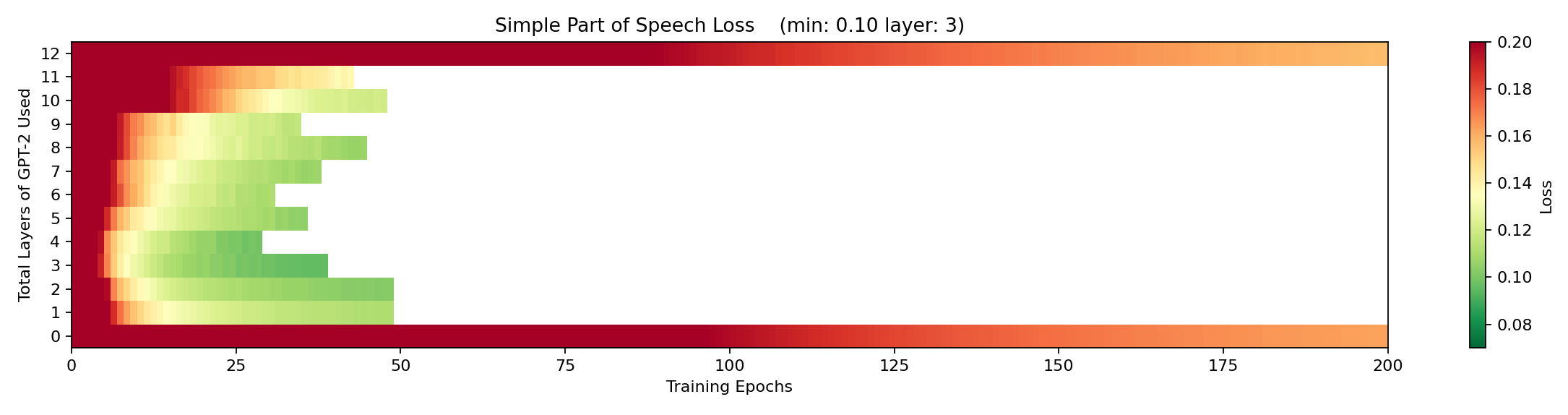

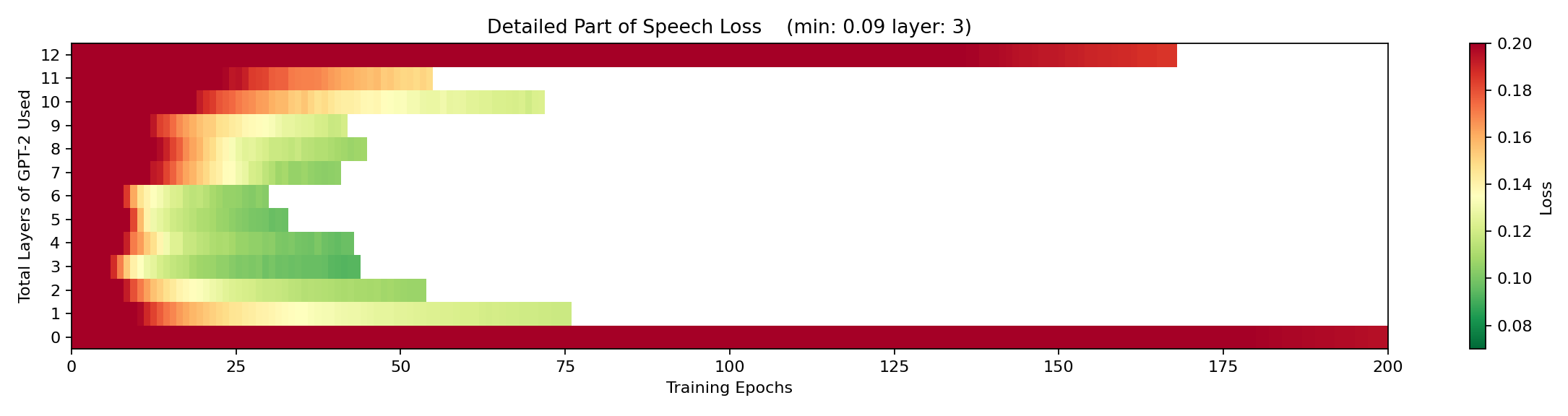

I also ran this experiment for simple part of speech and detailed part of speech and found these results:

We can see that it was slightly easier for the classifier to understand simple part of speech than to understand detailed part of speech. This makes sense because simple part of speech is, well, simpler. In addition, both simple and detailed part of speech have the best loss scores at layer 3, which indicates that part of speech is easier to extract from the initial embedding vectors than syntactic dependency is. This would be expected because part of speech can (often) be determined from simply knowing an individual token, but syntactic dependency requires that token, its position, and likely the other tokens in nearby positions. The embedding space could contain some part of speech information but it’s unlikely to contain much, if any, syntactic dependency information.

Hunting Wabbit (Heads)

Training the classifiers told me that incoming part of speech is iunderstood in layers 1-3 and incoming syntactic dependencies are understood in layers 1-5. So, I used truncated versions of GPT-2 (with the grammatical classifiers I trained on these trucated versions) to search for which heads played the biggest role in understanding grammar.

Initially, I followed the method laid out in the paper Are Sixteen Heads Better Than One?, which was also implemented by Huggingface in their Bertology example. This technique involves creating a ones tensor whose dimensions are the number of transformer layers and the number of attention heads per layer. Then I set this tensor to require gradients and multiplied the [i, j]th element of the tensor by the output of the jth attention head in layer i. Then I used back-propagation to calculate the jacobian of the grammatical classification loss with respect to the head coefficients. The idea was that if the derivative of the loss with respect to the coefficient of a given head is low, then this gives us some indication that that head was not extremely important for labeling the grammatical structure. And by contrast, if the derivative of the loss with respect to the coefficient of a head was high, then that head shoudlbe important for understanding the grammar of the incoming tokens.

Since the loss can be (and almost certainly is) a non-linear function of these coefficients, though, the derivatives with respect to the coefficients are only local, linear approximations of the importance of the heads. So, I decided to compare the results of this strategy with the impact on the loss when I pruned each individual head (which gives a definitive measurement of that head’s importance). And sadly I found that the coefficient derivative strategy did not do as good of a job of reflectiing the results as pruning the heads did.

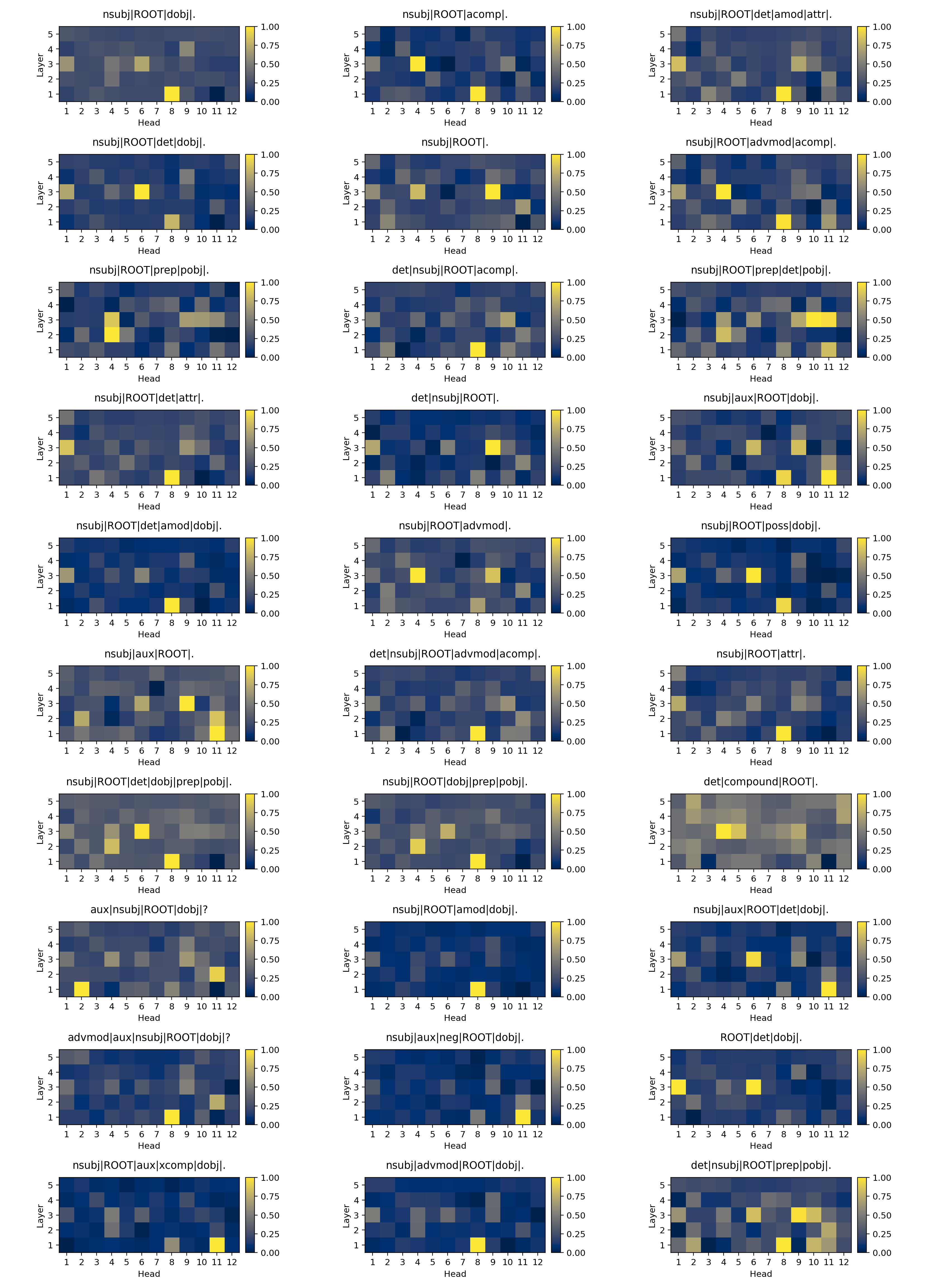

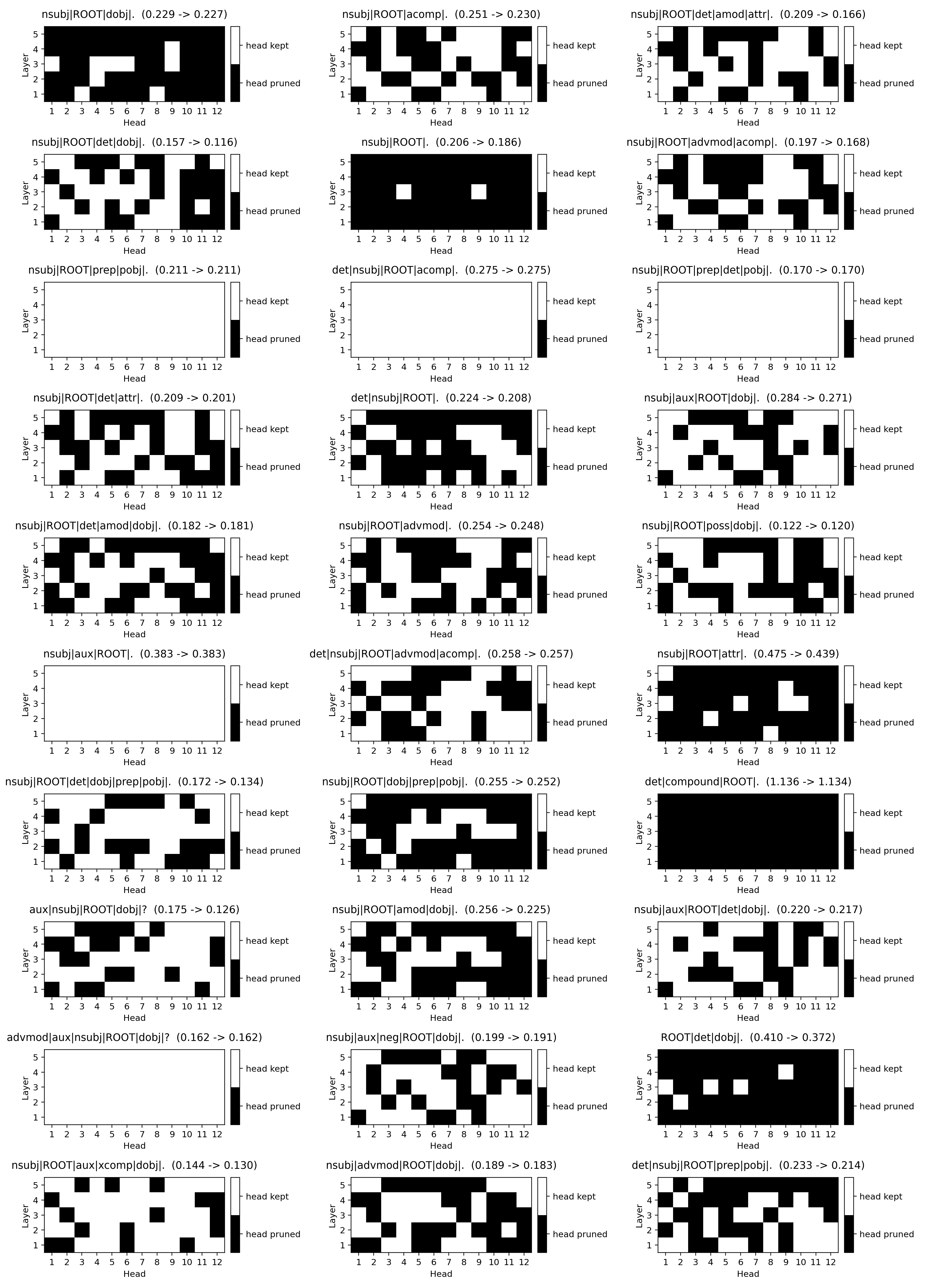

So, in the end, I just looked at the impact on the loss for each grammatical structure from pruning each head. And here are the impact maps for the top 30 syntactic dependency structures in my dataset:

Using these maps, I slowly pruned more and more heads out of GPT-2 for each syntactic dependency structure, so as to find which combination of pruned heads produced the lowest loss. Here are the best masks for the top 30 syntactic dependency structures. Note that black means the head is pruned and white means it’s retained):

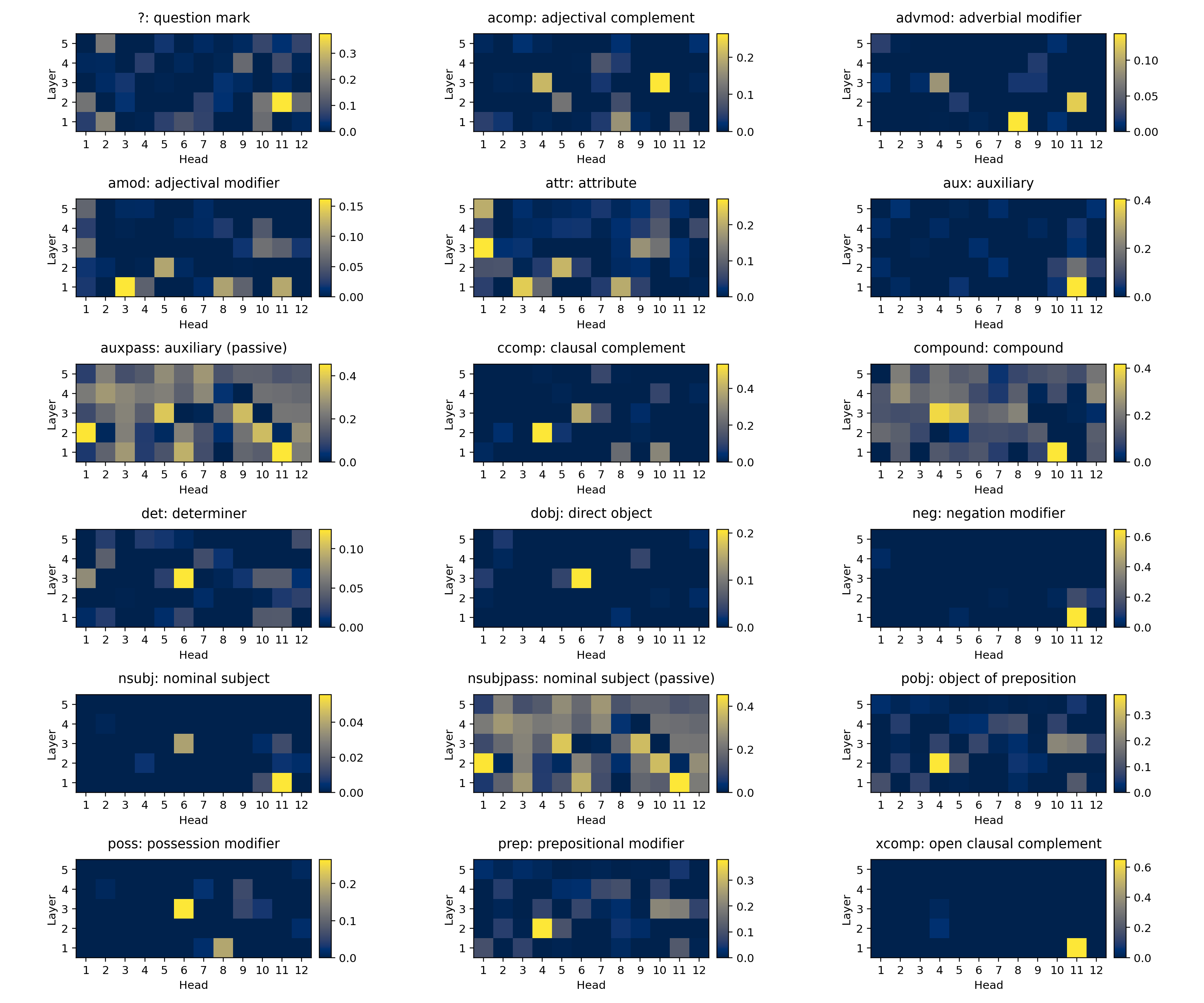

These masks seem extremely likely to give a map of which heads are involved in understanding each of these incoming syntactic dependency structures. We can see that similar structures require similar collections of heads, and that simpler grammatical structures require fewer heads than more complex grammatical stcutures. Finally, I looked for which heads have the most impact for structures containing each syntactic dependency label and I found that many labels seem to each be understood by a very small number heads:

In the future, I would like to test whether the heads needed for an given sentence structure are the same as the union of the heads needed for the labels comprising that sentence structure. I would also like to open up the individual heads for each part of speech label and understand how the query, key, and value weights map clusters of tokens in the incoming from the embedding space to clusters in the much lower dimensional key/value spaces. I have a suspicion that tokens in the embedding space will cluster into parts of speech and that these cluster boundaries will be critical in the projections to lower dimension key/value spaces performed by grammatical heads.